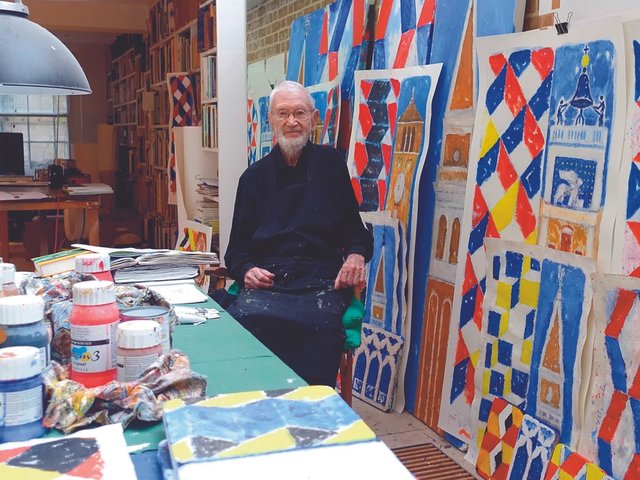

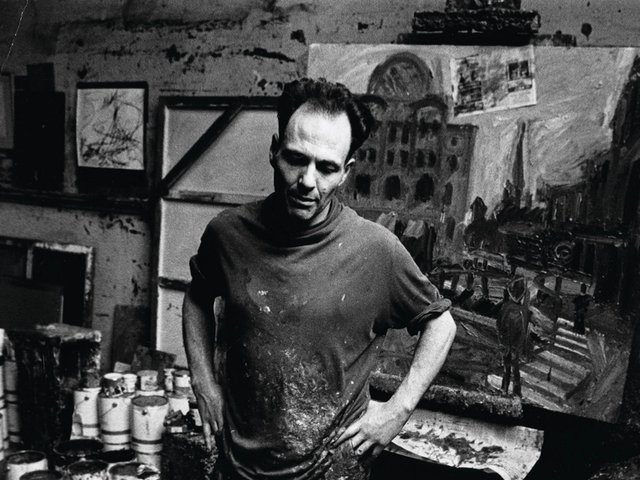

For seven decades, Frank Auerbach has been among the greatest of British painters. Last year, I staged a small exhibition of his work at my gallery in Venice, his first in Italy since he had represented Great Britain in the 42nd Venice Biennale in 1986, where he was awarded the Golden Lion. The exhibition was a selected survey of his distinctive drawings of London from the mid-1970s to the end of 2018, including ten of Auerbach’s drawings exhibited for the first time since they left the artist’s Camden Town studio and an important painting from 2007-08. This interview was conducted at Auerbach’s studio, where he has worked since 1954, in April 2019, in the week before the opening of the Venice exhibition.

The Art Newspaper: I think you downplay the importance of your preparatory drawings a little.

Frank Auerbach: I hardly know that I’m doing them. I throw away 95% of them. I let them pile up and then I go through them. If some seem a bit interesting, I keep them. I sometimes have [Ernst Ludwig] Kirchner in mind, who has left thousands of perfunctory drawings. You see them everywhere. If he had thrown away 95% of them, we would have had some extremely intense drawings. Done as adventitiously or as accidentally as all the others, they were drawings for paintings and ideas for paintings—and some very good drawings were made as a result. I’ve tried not to leave thousands of perfunctory drawings. It wasn’t that at the time I thought: “Oh, this is good drawing.” At the time I thought: “Well, this is an idea—I think it will help me with my painting.”

On the other hand, very often the coloured ones are not made in one go. I often start on a pencil drawing, and then perhaps add ink and colour over the top. As I move on to the painting, which takes ages and ages, and as I learn a little bit more about the subject—and when I say the subject, I mean the subject in plastic terms—the drawings get better as I go along. If I’ve done 70 drawings and I do the 71st, it may sometimes have a little more profundity than the drawings at the beginning. Sometimes a perfunctory scribble can be much more helpful than a “good” drawing. What tends to happen to me is that I go to a drawing because I need an idea for the painting. And an idea that I haven’t already got, because the whole process of painting is, for me, surprising myself.

Two 2006 studies in ink, crayon and pencil for Auerbach’s Park Village East series Courtesy Private Collection, London, and Alma Zevi

It’s not a routine thing. I’ve done many more drawings for some paintings than for others. I don’t do them in a sequence. Sometimes one keeps being pinned up, because it’s more helpful, for a month, and others are changed all the time. It’s very much a working process, and these drawings are the evidence of a working process.

Can you tell me about the drawings in the All Too Human exhibition [that toured the Picasso Museum in Malaga, Tate Britain and the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest in 2017-19]?

They seemed to me to be interesting drawings. And they seemed to me to be interesting also in their relationship to the painting they were studies for. I can only hope that that has happened more often than not. Because all my paintings, even from the beginning, have been photographed; I’ve been aware of where they are, and I know every single one of them. The drawings were mostly thrown away and a few scattered, or I’ve given them away.

Are you saying that the drawings are always studies for the paintings?

Those little drawings are, yes. One of the greatest joys in the world is Sleeping Girl [1654] by Rembrandt at the British Museum, which I know people think can’t have taken more than ten minutes to do. The fact that something is a quick drawing doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s slighter for it. Sleeping Girl is one of the greatest drawings in the world. If you made the list of the 100 greatest drawings—and there are many great drawings in the world—that would be one of them.

You said that sometimes you start with pencil?

Yes, and the next day I might go and add some ink. And then the day after that work on it in colour, so there are several sessions.

Do each of those sessions take place outside? Or just the pencil?

The process is, basically, I go outside and do a scribble. It feels as though I’m drawing for five minutes, but if I look at my watch, I find that I’ve been out for 35 or 45 minutes. And then what happens is that I look at the drawing, and I remember what it was that I reacted to. I haven’t got much of a visual memory, I realise, with the passage of time, and as I’m coming up to 88, I think it’s likely that that is the case. I also think that’s one of the reasons why I find it so fascinating to record and to draw. If I’ve done a hundred drawings and been working on the thing for months, then as I stand in here [the studio], I begin to have specific memories of the relationships of the forms. And of course, it isn’t a question of recording, it’s a question of invention. The only reason that I look at things is to give more quality to the image I’m making.

Auerbach's 2018 study for his painting From the Studio Courtesy of Alma Zevi

An arbitrary image, made simply on the basis of art history and geometry and so on, is a relatively dead thing. An image that’s made with the contradictions of life, where everything is not where you expect it to be, where things are irrational, where the light changes, where things are in awkward places that don’t fit in with the coherence of the whole, is much more likely to have an individual living character. That is why I like to have people there when I’m painting them, and that is why I like to look at real things when I’m working from other subjects.

It has even been the case when I’ve made one or two paintings from paintings. I made the large painting from the small Rembrandt Deposition [1632-33] and, even then, I went and drew the Rembrandt and came back and worked from the drawings of the Rembrandt. I didn’t sit in front and copy. I tried to dramatise my personal understanding of the forms that lie behind the surface.

I think I’m getting close to saying something that’s true of everything that I do. It’s not a visual thing—we get visual information, you identify yourself or information it refers to, and then you try and find some way of dramatising this corporeal, solid reality. That’s what the drawings are there to feed into. I don’t copy the drawings; they remind me of what I saw, so that I can re-imagine it as sculpture, as architecture, and make an image out of that re-imagination on the flat surface. Which is a complicated way of putting it, but that’s why a painting works sometimes. Some great paintings we never get fed up of, and that’s because there’s a very complicated process behind them, whether slow or quick.

Do you still draw from Old Master paintings or in the National Gallery?

Now I don’t do anything except my painting and practical things. I became well-off too late to adjust. I’ve never been able to employ anybody to do anything. So all I do is work and a little bit of shopping. Going to the National Gallery—it would take up all my day and all my energy. I used to get up at about five o’clock in the morning and do drawings. I haven’t got the energy to do that anymore. In the last few years, I’ve only dealt with subjects that are 20 steps away from the studio.

So I’m painting very close to my surroundings, and I’m enormously lucky to have people to sit for me. Once every five years, I think: “Well, perhaps I should have fewer friends sitting for me,” and then even if they go away for a week, I realise there’s something missing. What one hopes feeds into the painting is the varying living, changing matter of life, and one hopes to catch some little corner that one hasn’t seen before. After all, what is portraiture, except finding new deviations from the norm? You know, there’s a “classic head” and then you look—nothing about the person’s head is “classic”—and it gives you a whole new geometry and a whole new expression. And that’s the sort of painting I like. Because even Mondrian has that for me. It’s got nothing to do with abstract design. It has to do with sensation.

I heard Bridget Riley talking on the radio yesterday morning. She said that the sensations which feed into her paintings are not so different from a walk in the country where there’s light and shadow. We’re almost the same age, we were born within a week of each other, and we worked in the same room at the [Royal College of Art].

Did you ever draw from reproductions of paintings?

I think a little bit—I must have done at various points, but not very often.

Perhaps as a student and a young man? Or intermittently?

Yes, I did a bit. I think I was lucky in the art school experience I had. Many of the teachers were limited, but there were intelligent painters teaching in art school, and in my second year as an art student at St Martin’s, Freddie Gore, the son of Spencer Gore, gave some lectures about Old Masters—very good, intelligent lectures—and then sent us to the National Gallery and said we should do our own version of a painting there. And for some reason, as a young, ambitious show-off student, I did a version of El Greco. It was a picture of birds caught in barbed wire. I think I may have done that from a reproduction.

But the more I went to the National Gallery, the more I realised that drawing from reproductions just doesn’t work. Reproductions are so misleading that you simply can’t get from them the moment you get from the picture. And even when I did one or two pictures and got a photograph to help me in addition to the drawing, I found myself doing pencil scribbles all over the photograph to get it a little bit more like the picture. You used to just walk up and buy a picture over the counter, a photograph.

I thought it was one of the great miracles of life, that you could just walk into the British Museum Print Room and ask to see a case of Rubens’s drawings or Rembrandt’s drawings, and you didn’t have to have a certificate or a letter or a qualification or anything. The same is true of the V&A.

The Courtauld Gallery also has an amazing collection of drawings. When I was a student at the Institute, we were lucky enough to have seminars in the Prints and Drawings Room and it was really fantastic.

Also, the Queen hasn’t got a bad collection. The Royal Drawing School goes to Windsor Castle and are able to handle the Leonardo things once a year. Yes, there are lot of good drawings in the world… The actual idiom of paintings is definitely changed. Drawing seems independent of time. Nobody could mistake a 21st-century painting for a 15th-century painting. There was a very intelligent exhibition of drawings at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, curated by Michael Craig-Martin. And it made it absolutely plain what I think I had known before and that he had known before; that a drawing is a drawing. It hasn’t changed. They’ve got hundreds of Dürer drawings at the British Museum. There are some which have obviously been done by the artist in half an hour—the way you might see a brilliant drawing by Hockney done in a restaurant or something of a person sitting opposite him. And although it says, “AD” in the corner, it could have been done by Picasso. Drawing is drawing. It is remarkably timeless, at least in the Western traditions, since Giotto.

Do you think there is more freedom in drawing or more spontaneity. Or is it something else?

It is more private. If you look at Tintoretto’s drawings, he drew very quickly these marvellous compositions of people reaching down and dragging children over the walls, of sieges and battles, because he wanted a particular figure. These quick, brilliant drawings, of figures turning—some of which El Greco pinched and took to Spain to use the same poses—were done, I think, to feed into his painting. For no other reason, they’re marvellous drawings. And, in fact, for me, some of the elaborate presentation drawings of Michelangelo don’t work all that well—the ones that he gave to his friend which are tidied up and over-elaborated—whereas the sketches of architectural details and backs turning and so on, done urgently, in order to compose a figure on the Sistine Chapel, they’re done by the greatest genius and greatest draughtsman that ever lived.

Biography

Born: Berlin, 1931, lives in London

Training: St Martin’s School of Art, London, 1952, Royal College of Art, London, 1955

Key shows: 2015: Tate Britain, London; 2007: Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK; 2001: Royal Academy of Arts, London; 2000: Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen, Denmark; 1995: National Gallery, London; 1989: Vincent Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam; 1986: Kunstverein, Hamburg, Germany; British Pavilion, Venice Biennale; 1978: Hayward Gallery, London

• Alma Zevi has a gallery in Venice, a showroom in London, and a project space in Celerina, Switzerland